What would a 21st-century Central Park look like? These winning entries reimagine the New York landmark

By Justine Testado|

Tuesday, Nov 27, 2018

Related

New York's Central Park is a prominent example of exploring the role of a large, historic urban park in today's cities. In LA+ Journal's latest Iconoclast Competition, students and professionals were invited to send their ideas of how they would recreate the infamous park, which has been fictionally devastated by eco-terrorists, the competition brief states.

The ideas competition attracted 193 submissions from 382 entrants representing 30 countries. The acclaimed jury ultimately selected five equal winners, who will each receive a $4,000 cash prize. Check out the winning entries below.

“From megastructures to new ecologies and radical ideas for democratizing public space, the LA+ ICONOCLAST winning entries show how designers can move beyond the status quo of picturesque large parks and embrace the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century,” jury chair Richard Weller commented.

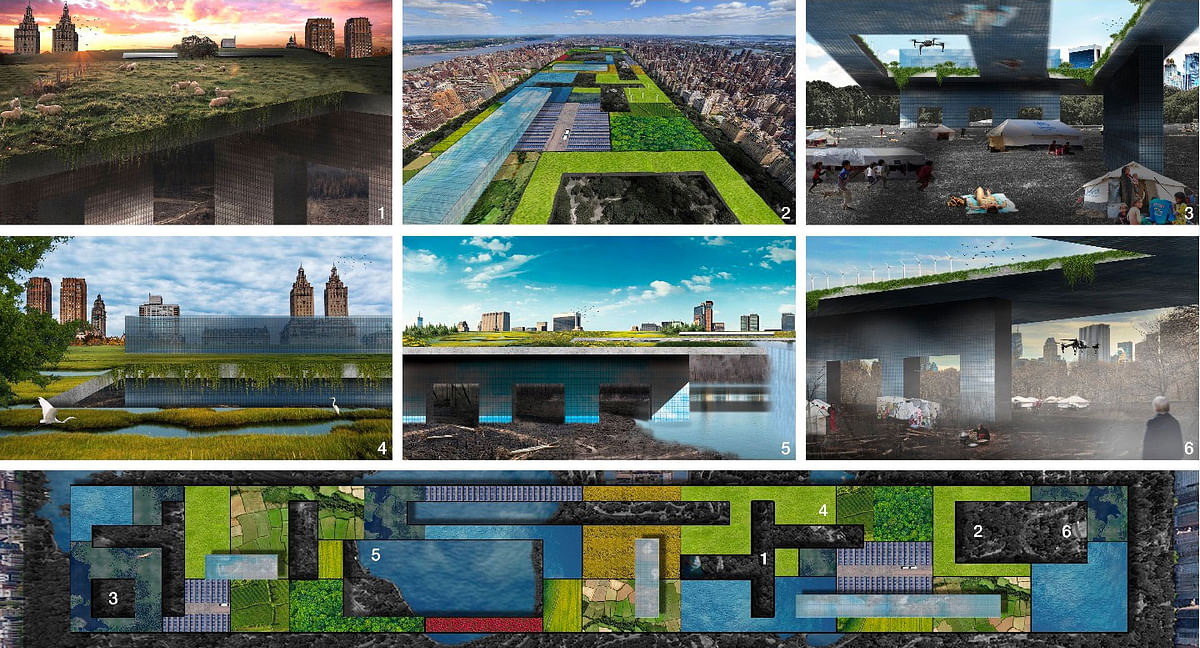

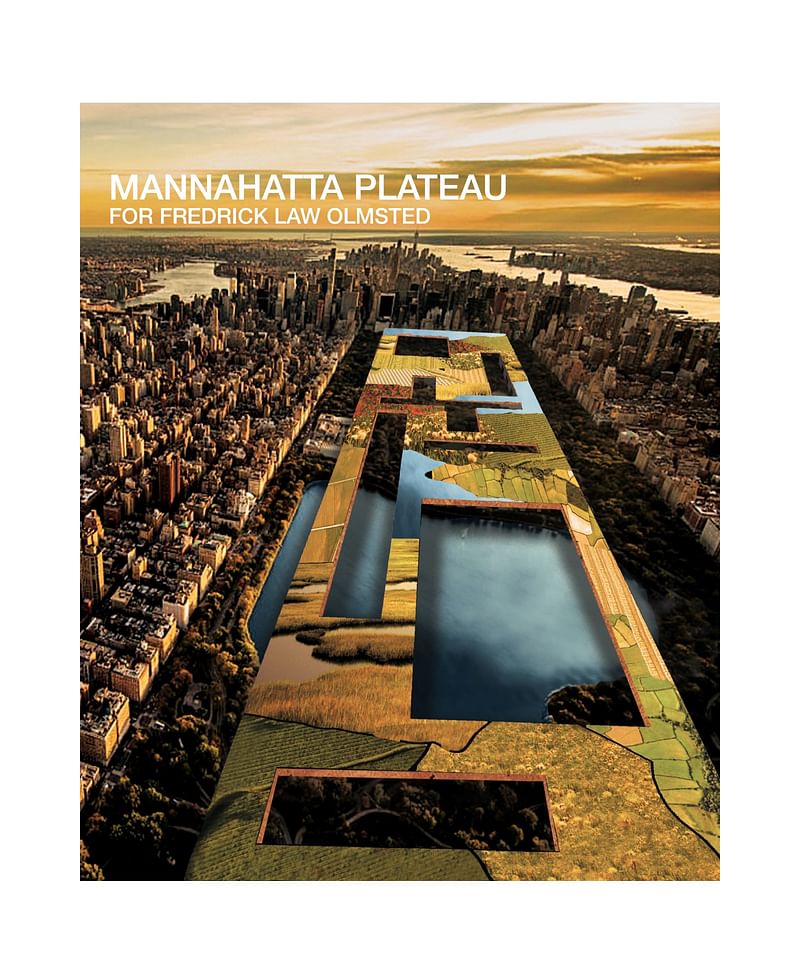

“MANNAHATTA PLATEAU FOR FREDRICK LAW OLMSTED: A Re-Enchantment for a Post-Apocalyptic Ecology”

by John Beckmann, Hannah LaSota + Laeticia Hervy - Axis Mundi Design | New York, USA

Project excerpt: “The MANNAHATTA PLATEAU presents a dynamic ecological vision of nature integrated with urbanism. The ravaged original surface of Central Park is left as a regenerating wilderness, a temple to the raw power of nature. Built over it is a green mega-structure, a plateau that supports a raised parkland consisting of a patchwork of abundantly diverse interconnecting environmental zones. The bold, linear aesthetic of the plateau offers a new perspective upon the wilderness that lies partially revealed beneath its cut-out surface. The 200-foot-high structure is inscribed by the lines and scale of the city itself – the typical Manhattan building lot (25 x 100 ft) serves as the basic modular. The street grid is celebrated by being projected across the park’s surface, yet the rigid geometry of urban forms is broken down into subsections defined by the flowing lines of nature. In addition, supporting structures containing vertical circulation are clad in glass that directs light back onto the dystopic landscape below, whilst optically blurring the distinction between nature and architecture...”

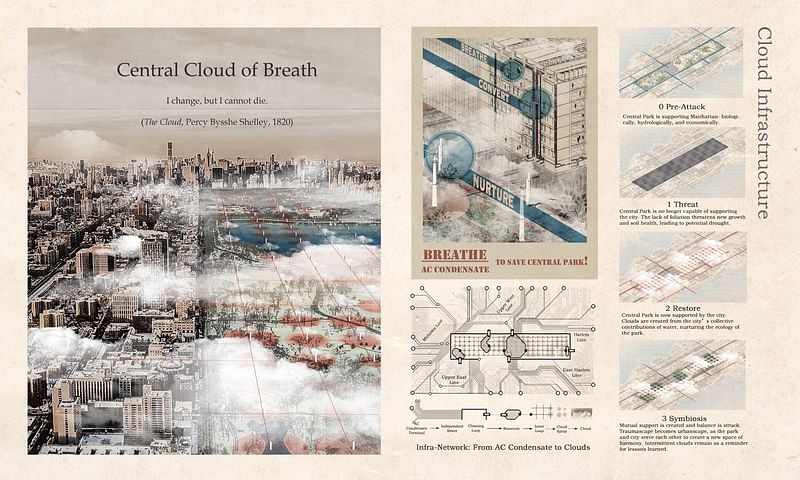

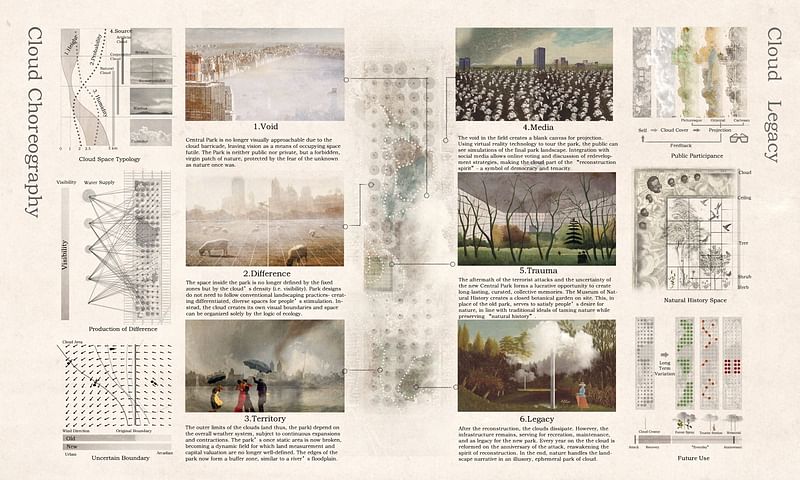

“Central Cloud of Breath” by Chuanfei Yu, Jiaqi Wang + Huiwen Shi - South East University | Nanjing, China

Project excerpt: “After the terrorist attack, Central Park lost all of its trees, causing the microclimate to change dramatically. The increase in evaporation due to the loss of the tree cover poses a problem for any reconstruction idea. Our short-term plan proposes creating a layer of cloud over the Park. The layer—meant to decrease the evaporation of water and protect the reconstruction of the ecosystem—will be created and maintained by artificial-cloud infrastructure. Water used in the plan will come from the AC condensate of Manhattan office buildings – essentially the water vapor exhaled by people. In this way, every New Yorker is part of the great ‘Breathe to Save Central Park’ plan...”

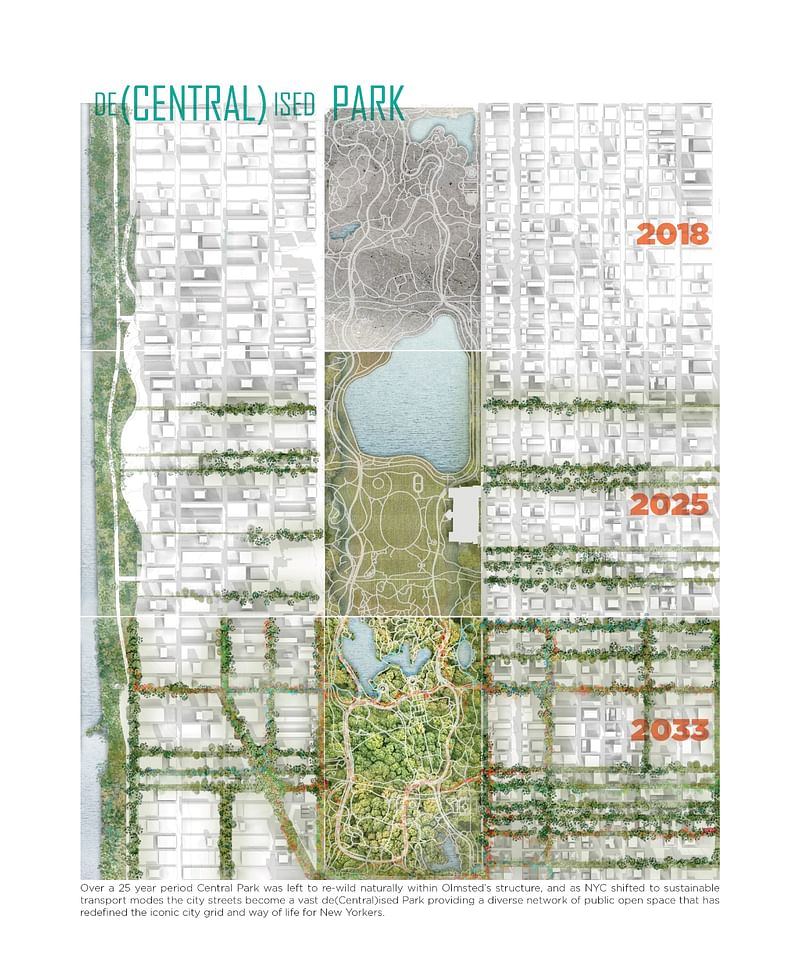

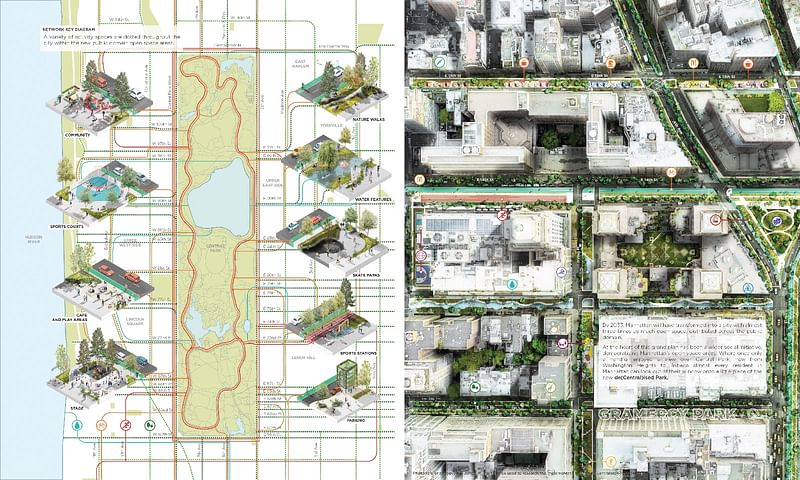

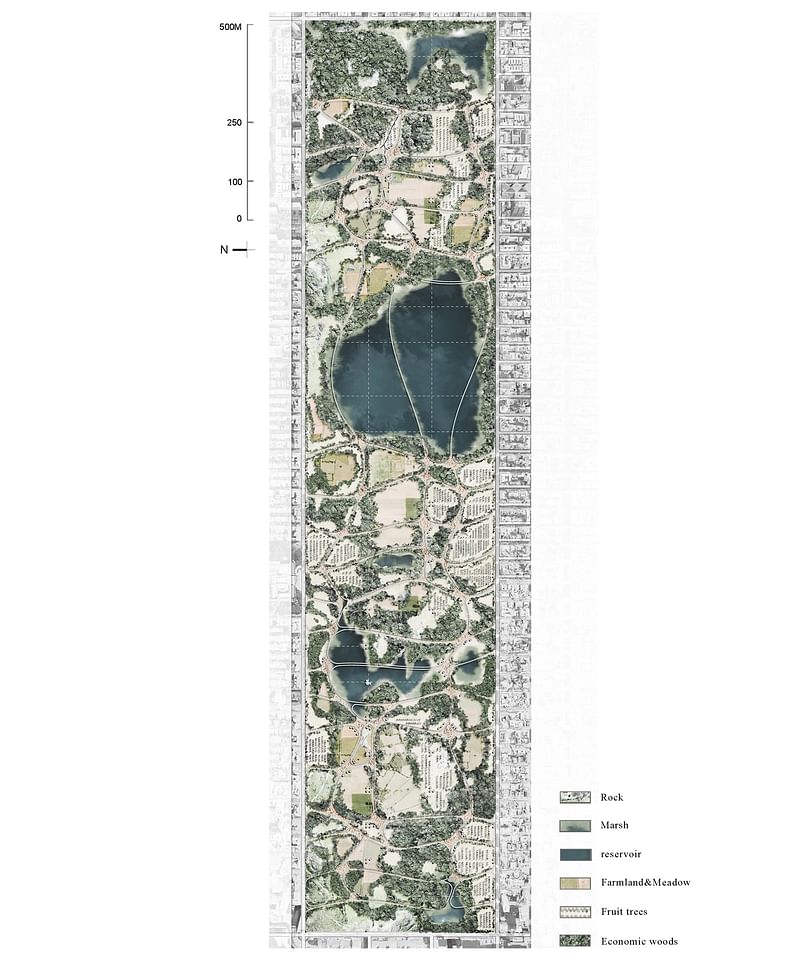

“De(Central)ised Park” by Joe Rowling, Nick McLeod + Javier Arcila - e8urban | Sydney, Australia

Project excerpt: “Following the 2018 eco-terrorist attack on Central Park, New York City authorities—acknowledging the public’s concern about the depletion of global resources—embarked on a radical program to reduce the city’s environmental footprint. It was decreed that Central Park would be encouraged to rewild naturally within the existing structure of Olmsted’s Central Park masterplan. Furthermore, it was decreed that by 2033 all vehicles within Manhattan would be electric with ride-sharing incentivized. This bold move had the result of freeing up a vast area of formerly car-dominated public space, namely vehicle carriageways, which the city converted into new urban parklands with an area twice the size of the original Central Park – a new de(Central)ized Park. This ambitious plan implemented over a 25-year period saw almost 75% of the streets within Manhattan replanned with vastly reduced roadways, dedicated cycleways, and new diverse open-space ribbons and dwelling spaces radiating out across New York City...”

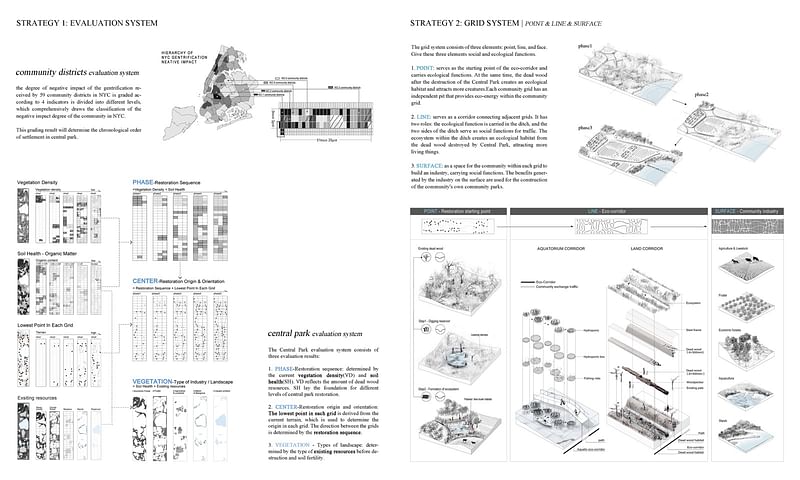

Song Zhang + Minhzi Lin Song + Minzhi | Chicago, USA

Project excerpt: “We believe that eco-gentrification is caused by environmental inequities. Low-income communities need fair access to green spaces, but they are also afraid of the adverse effects of eco-gentrification. In addition, communities may lack autonomy in the construction of community parks, and lack the ability to resist eco-gentrification. As a typical representative of high-end parks, Central Park has enough influence to respond to these issues. The concept we propose is to link Central Park with 59 communities in New York as the main force in the construction of Central Park, giving them access to funds raised through their Central Park activities that will allow them to improve green spaces in their own communities...”

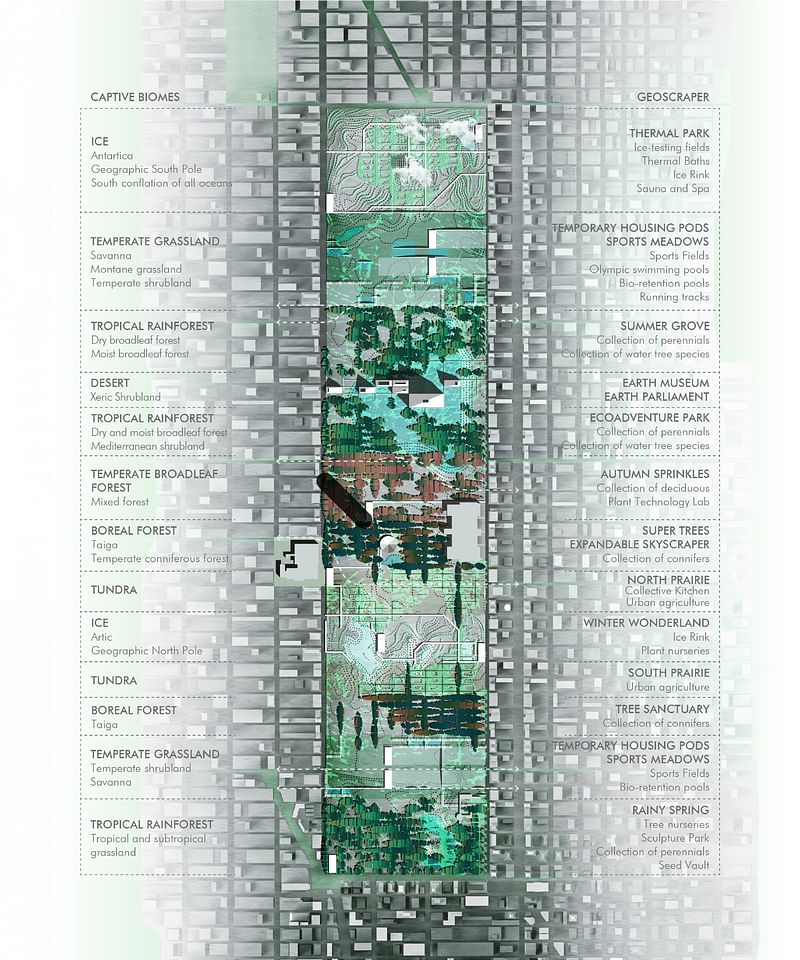

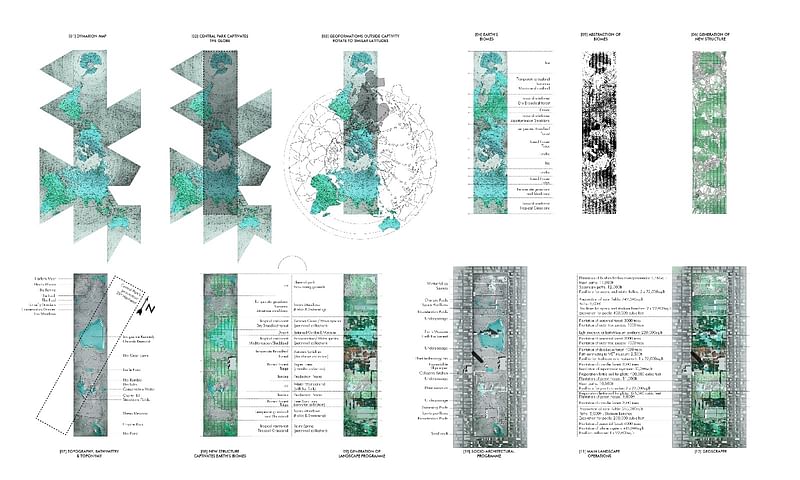

“THE GEOSCRAPER OF THE CAPTIVE BIOMES” by Tiago Torres-Campos | Edinburgh, UK

Project excerpt: “Looking Back: One Hundred Years After the Eco-Terrorist Attack

New York: April 23, 2118

On this day, one hundred years ago, Central Park’s vegetation was suddenly wiped out. In a few days, one of the world’s most cherished landscapes disappeared without a trace. The Gaians were extremely violent in drawing attention to the planetary destruction we were causing.

Periods of mourning following brutal attacks are often pivotal in the collective lives of cities. They are times of grief, sorrow, and absence, just as they are times of rebirth, hope, and reconstruction. Above all, they bring about great, meaningful transformation.

Soon after the incident, the temptation to grid over the park was tremendous. The temptation to relocate the green lung elsewhere was even bigger. Yet we resisted. Looking back, we can proudly say that the “Geoscraper” – the Park’s affectionate nickname has remained what it had been since its inception on the city grid. Or has it? Instead of acting like a drawing master, the appointed landscape architect diverged from the designs of the Park’s founding fathers. While they restaged a state of virgin nature in the form of a 19th-century picturesque park, the landscape curator reignited a 40-year-old idea of that landscape as a giant horizontal skyscraper. From an Arcadian synthetic carpet, the Geoscraper evolved into a performative landscape machine whose first function was to capture the Earth’s biomes. These were then converted into a landscape program where alternative social and ecological values and functions were forced to coexist. Building upon the Park’s previous role as the center of one of the world’s centers, the Geoscraper also became an active place for geo-eco-bio-social experimentation...”

You can check out the winning entries in full and the honorable mentions here.

Jury:

Lola Sheppard (Partner and Co-Founder, Lateral Office), Charles Waldheim (Professor and Director of the Office of Urbanism, Harvard GSD), Jenny Osuldsen (Partner and Director, Snøhetta), Geoff Manaugh (Author, BLDGBLOG), Beatrice Galilee (Associate Curator of Architecture + Design, The Metropolitan Museum of Art), and Richard Weller (Meyerson Chair of Urbanism and Professor and Chair of Landscape Architecture, PennDesign).

Share

4 Comments

Erik Evens · Nov 28, 18 1:27 AM

How is the existing Central Park "infamous"?

Thayer-D · Nov 28, 18 2:31 PM

What a colossal waste of time.

Chemex · Nov 28, 18 3:57 PM

What an offensive project. Even implying that change is possible at Central Park is a slap in the face to NYC

gasworks · Nov 29, 18 3:48 PM

What an idiotic competition, totally waste of time on a false issue.

Comment as :