Ministry for All

Saturday, Sep 21, 20193 PM — Saturday, Dec 14, 20196 PMEDT

New York, NY, US | Storefront for Art and Architecture, 97 Kenmare Street

Related

Buildings are often positioned as beacons of progress and symbols of growth and power. Their foundations, dug solidly into the earth, aim to give shape to new visions for future social ideals and to frame the identities of the territories in which they are located.

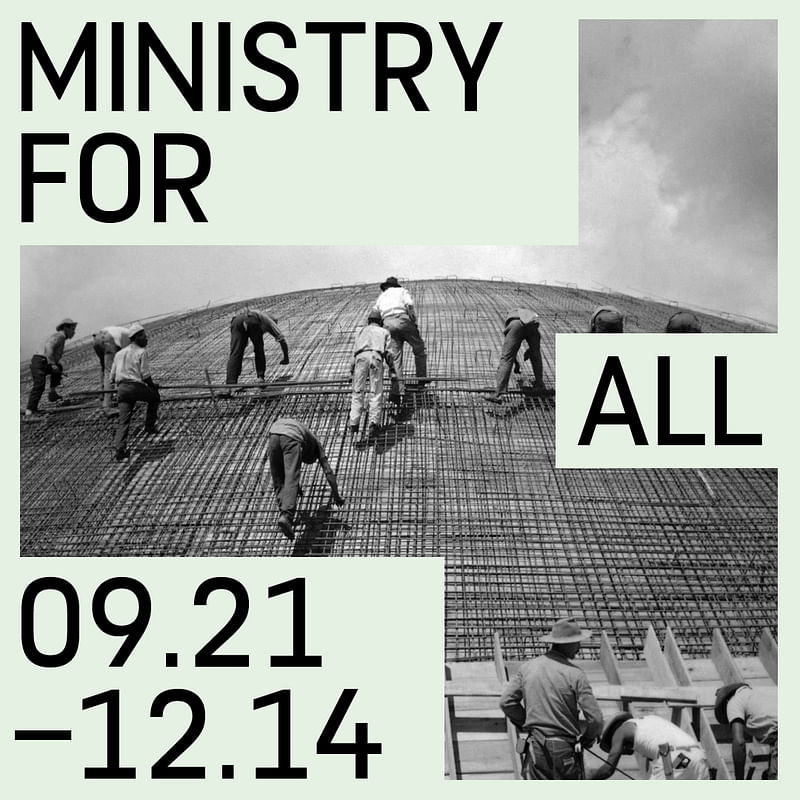

Ministry for All takes its title from the monumental work of civic buildings by architect Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012) that once stood as an emblem of social, political, and economic development in what would be Brazil’s new capital, Brasilia. Built between 1956-1960, the city was laid out in an open plan by architect Lucio Costa (1902-1998) to be a modern utopia in which all aspects of life had a distinct space, and all buildings had an explicit agenda.

As the new seat of the nation, Brasilia’s central district incorporated grandiose structures: a congressional house, a cathedral, a presidential residence, and the Esplanade of Ministries, which consists of a series of seventeen colossal concrete edifices that flank the Monumental Axis, the city’s central avenue. While the Niemeyer/Costa plan for Brasilia erected formal structures imbued with a sense of stability, the composition and nature of the Ministries changes from one administration to another, and their reconfiguration is often used as a political tool by those holding the country’s highest office. The physical presence of the structures remains constant, yet what occurs inside of them is perpetually in flux, ultimately shaping and influencing the social order.

Ministry for All pairs architect Carla Juaçaba (Rio de Janeiro, 1976) and artist Marcelo Cidade (São Paulo, 1979) in an indirect collaboration that exposes the physical infrastructures of Storefront’s gallery space in order to comment on the social and political foundations of the built environment. This site-specific installation, created entirely with Storefront’s existing infrastructural elements, undresses the gallery’s iconic facade to acknowledge the theatricality and vulnerability of architecture.

Juaçaba’s simple gesture of removing the facade’s concrete panels reveals the inner workings of the building. Its cladding is no longer on view from the outside; instead, construction materials such as insulation foam and plywood boards are exposed. By rendering these infrastructural components visible, Juaçaba’s intervention reflects upon the foundations that underlie systems of power. Cidade brings the concrete panels to the gallery’s interior, rearranging them to create new spaces, forms, and interactions. This layered installation extrudes the facade inward and allows visitors to walk through it, providing a different reading of its panels now that they are no longer performing their intended function. The artist repurposes the gallery’s protective shell, with its cracks, dirt marks, and graffiti, into a composition that alters the space, shifting the order of what we consider to be inside and outside, or public and private.

Acknowledging the limits of architecture can provide important lessons about how spaces come to be used differently from their stated intentions. Although exposing what buildings are made of might make them seem vulnerable, in recognizing their fragility we are reminded that it is the users who make them perform.

Together, Juaçaba and Cidade’s collaboration serves as a conceptual and poetic critique on the resilience of architecture that ultimately asks a crucial question for the future of Brazil and other societies around the world: how do we build social and political systems that work for all?

Share

0 Comments

Comment as :