A closer look at Daniel Buren's colorful intervention at the Fondation Louis Vuitton

By Justine Testado|

Friday, May 13, 2016

Related

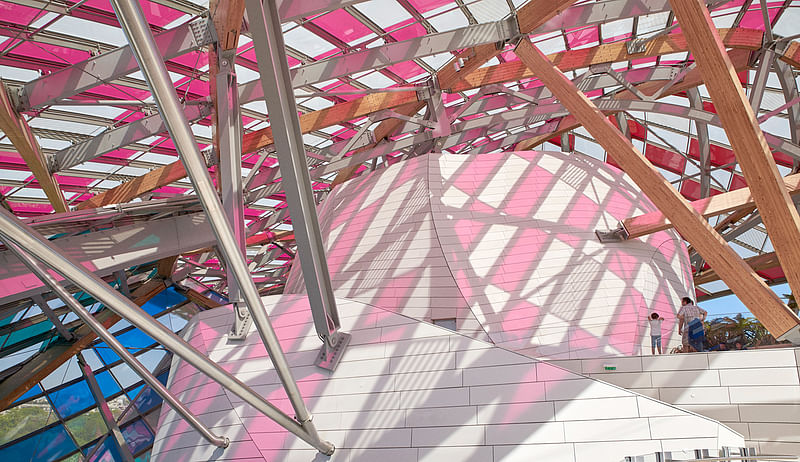

Thanks to in situ artist Daniel Buren, the white glassy curved sails of the Gehry-designed Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris have received a generous splash of vibrant color — or 13 colors, to be exact. And just in time for the summer season. Developed in collaboration with Frank Gehry, Buren's temporary piece, titled “The Observatory of Light“, made its official debut this past Wednesday. It took 29 nights over a period of five weeks to apply the dyed filters and white 8.7 cm-wide strips throughout the building's 3,528 glass panes.

In developing the intervention, Buren wanted to visually challenge the structure, while also respecting it. The piece adds a new playful interaction of contrasting color, unexpected mirrored reflections, transparency, and lighting to both inside and outside the building. Visitors who stop by the Fondation now will get to experience the Fondation building with a refreshing one-of-a-kind perspective.

Keep reading for snippets of a conversation between Daniel Buren and FLV Artistic Director Suzanne Pagé, featured in the accompanying book Daniel Buren, “The Observatory of Light”, co-edited by Fondation Louis Vuitton / Editions Xavier Barral.

Suzanne Pagé (SP): “You and Frank Gehry have known each other for more than forty years. Today you have entered into a new dialogue, in situ, after the singular and more distanced one in Bilbao. What was your perception of this building, which you have always been enthusiastic about? [...] What is it that interests you in the idea of reviving that now, ten years later?”

Daniel Buren (DB): “You were there. It was in June, I think. Frank Gehry asked me to come. He wanted to tell me how keen he was for me to do something. He imagined types of flags floating amidst his ‘sails’ on two of the terraces, partially covering them. I told him that I needed to take a closer look and that I thought it was already too late for the opening. The flags or other objects in the wind, I couldn’t imagine that. However, the use of coloured filters could be spectacular and interesting because of the complexity of the structure, of what is going on over them. I really like this controlled chaos. The transparent glass panels – well, they’re silkscreened to attenuate the sunlight a bit – that cover the entire structure, along with the waterfall that disappears under the museum, are, in my view, the most successful parts. There’s nothing like that in Bilbao. The only thing the two buildings share is that both are the work of the same architect.”

SP: “The scale, too, is different.”

DB: “You can’t compare them. In a way, the idea of turning everything here towards the interior by using multiple terraces, which mean that you can be outside while being in the museum, is a rather amusing one and it opens up a whole lot of possibilities. I had nothing specific in mind but I was sure that there were a thousand ways of intervening. So, I thought of filters, which were perfectly in keeping with the spirit of the construction. Of course, Gehry still had to agree to someone touching his structure. But then, he did tell me: ‘You know, when I make a museum, it’s for artists to do what they want in it, to question it, to destroy it.’ If I was allowed to touch the glass, then I could get to work. I made a model of the project and in August I sent it to Frank, as I did to you, in fact. He answered me the same day: he thought the project was magnificent, but he added: ‘We need to give the public a bit of time, at least a year, so they can get used to the architecture. After that, you’ll be free to transform it.’ I was expecting him to say that. Gehry naturally wanted the museum to be seen as he had designed it, before letting someone touch it. That’s how it started. For me, then, it’s great to be going back to this project.”

SP: “Exactly, what kind of provocation does this building represent for you? Did it constrain you, and did you try to adopt certain principles or, on the contrary, maintain or even create tension?”

DB: “I knew, even before I made it, that my project would visually challenge this structure. At the same time, it also respects it. It’s obvious that the terraces are going to be transfigured on sunny days by the projections, which will completely change what we already know about this new structure. The original construction is very monochrome – creamy. Nothing interferes with the golden-brown ambience. Especially in the daytime, because there is no artificial lighting. Adding colour to this structure will radically change the impression it gives. Without physically transforming anything, simply because of the quality of the glass and its curves and dips, the forms will shift even though nothing has been changed.”

SP: “Your basic vocabulary is quite apparent in your project here, that well-know ‘visual tool’ as you call it, with the alternating 8.7 cm stripes, colour-light and transparency and, of course, mirrors. Transparency and mirror effects are exactly what we find in Gehry, too.”

DB: “There are all kinds of mirror effects that do not come from mirrors but from the glass. Almost everywhere there are reflections. If we do not notice this effect that much, that is because it seems obvious, with all this glass, the beginnings or endings of corridors. The doors and glass walls set up a multitude of reflections, and what is reflected is what is above us, as I said, dressed in a monochrome, or rather in gradations going from off-white to the golden-brown of the beams. It’s so fluid, so harmonious that you hardly notice it, it all seems so normal. What I am sure of, though, is that when the sails are coloured, these reflections will become much more present and will make these ‘dormant’ mirrors that are positioned all around us more active.”

SP: “Did Gehry’s decisions set rules for you here? How do you plan to assert yourself in the face of the architecture?”

DB: “That’s something which has never bothered me. In most of my pieces, especially the ones articulated mainly around the architecture of a given place, I remain dependent. I play with it while never really trying to dominate. If one side gains the upper hand, it’s usually the architecture. The problem here is that Gehry’s proposition is, if I can say this, barely visible. That’s why I’m sure that when a bit of red or yellow appears in the reflection of the roofing over a stairway, or over the restaurant, say, people will realise that they are being reflected, whereas now you have to be very attentive to see that the transparent sides are all latent mirrors.”

SP: “You have chosen thirteen colours and given us a certain latitude in positioning them on the two-sided sails. Am I right?”

DB: “Yes and no. When we were choosing the folded sails, I always specified the colour – light or dark – and, having established this principle, as I thought it would be very similar either way, I left the freedom to decide to position the light above and the dark below, or vice versa.”

SP: “Your choice of colours is very precise, however.”

DB: “Yes, but at the same time I’m playing with existing materials that have limited possibilities. Also, there are some colours, like the reds or the blues, where you can barely make out the different shades, unless you put them side by side. If, say, I position a sky-blue sail not far from a sail that is in a slightly darker blue, the nuance is so subtle that nobody will see the difference. However, when they’re projected onto the walls or the floor the difference between the two blues will be visible. Then the true colour appears. Under the sky, the value is slightly different. That’s what I like about these filters: everything is multiple and subtle. The colours that are chosen are basic ones – except when you have the idea of a dark shade and another lighter one. The blue must be a blue, the green, a green, the red a red, the orange an orange. There’s no confusing bold colours.”

SP: “You have the mastery, the total awareness, but paradoxically, it’s precisely because of this that the unexpected, that miracles can happen. That goes for Gehry and for you. For any true artist.”

DB: “Miracles happen when the project is a success. If everything is rigorous enough, if it follows the logic from start to finish, then the person looking at the work is free. If there is the slightest accident, physically or mentally, in the construction, the slightest grain of sand in an engine that was running fantastically smoothly, everything can go wrong. The viewer can no longer be free; all they can think about are the causes of this accident. Everything, in a work of art, is connected, and the viewer or listener has to keep their freedom.”

RELATED NEWS Frank Gehry is the first architect to win the Harvard Arts Medal

RELATED NEWS James Corner is designing a field of ICEBERGS at the National Building Museum this summer

Share

0 Comments

Comment as :